When we add information we find in other ancient Near Eastern texts (such as The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Epic of Etana), we learn that wanting to make a name for oneself is an honorable endeavor, characterized by good deeds and great accomplishments. Genesis 11 is the only time in Scripture where people are making a name for themselves, but that does not mean it is inherently an offensive act. On a few occasions, it refers to God making a name for someone (like Abram in Gen. In the Old Testament, it is used most often to refer to God making a name for himself-a great name that enhances his reputation (see Isa. Making a name is a phrase that speaks of honor and admirable reputation. People “make a name” for themselves through anything that would cause them to be remembered in future generations. Genesis 11:4 reads, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.” This story is about something more.īoth potential offenses of the builders-pride and disobedience-begin to look like shaky explanations when examined closely. I eventually came to the conclusion that such a reading, despite its long tenure in Christian and Jewish interpretation, doesn’t stand up when subjected to close scrutiny, including recent knowledge gleaned from ancient Mesopotamian texts. I felt that something important was missing. To be sure, humans are guilty of such wayward behaviors, but in this interpretation, the tower is reduced to a metaphor of rebellion and overreaching.

The inevitable lesson warns against the dangers of overweening pride, the hubris of ambition, and the folly of disobedience. They were judged guilty of the gross sin of pride and, in some readings, of refusing to fill the earth, thus disobeying the command of Genesis 1:28. Today, and for centuries in the past, the common interpretation of this passage has been that the builders were attempting to storm the heavens, not unlike the Titans of Greek mythology, with any variety of intentions depending on the imagination of the interpreter. It is one of those stories that assumes a significant amount of cultural knowledge on the part of the reader, without which we intuitively impose our modern assumptions that can lead to skewed interpretation. It is an amazing story-pivotal, yet often misunderstood. Years later, in my doctoral work, I decided to do my dissertation on this passage that thrived in popular imagination but was underserved in academic treatments.

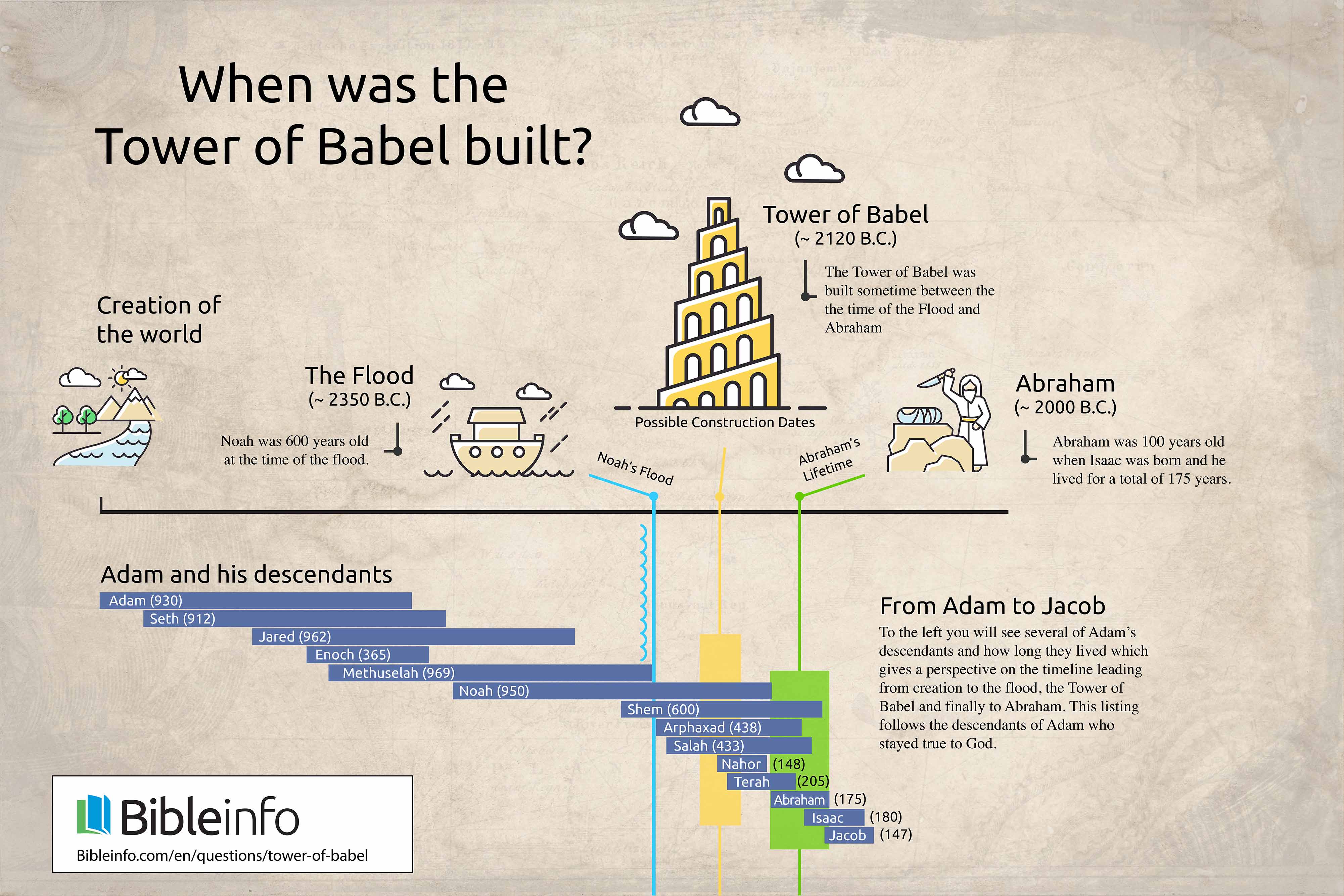

The picture was colorful and vibrant, depicting a crowded and lively scene of human industry-smoke arising from countless kilns, oxen and men carrying heavy loads of brick, and workers using scaffolding and ropes to build a structure many stories high. An artist’s rendition was among the few pictures in my Bible, and I spent many a sermon pondering it. In this Close Reading series, biblical scholars reflect on a passage in their area of expertise that has been formational in their own discipleship and continues to speak to them today.Īs I was growing up in church, the account of the Tower of Babel (Gen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)